Egypt’s Valley of the Kings is one of the richest archaeological sites anywhere. The World Heritage Site boasts 65 tombs cut out of the steep limestone cliffs, including the most famous of all: the tomb of King Tutankhamun. Torrential downpours and earth tremors can threaten the stability of the tombs and cause dangerous rockfalls. To measure the stability of the valley’s geology, archeologists turned to the internet of things (IoT) technologies to monitor the valley’s geology in order to preserve the tombs and minimize risk to the thousands of tourists who visit the valley every day.

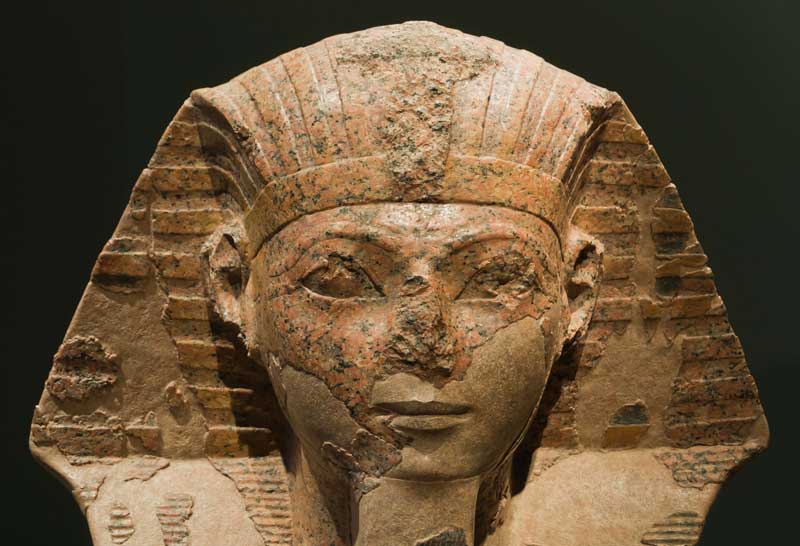

In 2018, researchers from York University, ETH Zurich, and the University of Basel began investigating geological features and activity in the valley. One project focused on a rock column in the fractured cliff face around the tomb of Queen Meryet-Hatshepsut, the “great royal wife” of pharaoh Thutmose III and the mother of Pharaoh Amenhotep II.

They installed a suite of solar-powered wireless sensors made by the Spanish technology company Libelium. Starting with Libelium’s Plug & Sense Smart Agriculture Pro weather station, the researchers added a seismometer and a dendrometer – normally used to measure tree growth, but repurposed to measure the width of cracks in the rock.

Libelium’s Plug & Sense devices had already been used to monitor light levels and humidity around two priceless tapestries at the Museo Provincial de Huesca in Zaragoza, Spain. The sensors sent data on light levels and humidity over a 4G connection to a website where it could be monitored in real time.

In Egypt, six sensors collect readings every 15 minutes around the clock on a wide range of environmental parameters: air temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, surface temperature, surface moisture, crack width, wind speed and direction, rainfall, and solar radiation. Data is recorded and uploaded to a remote server over a cellular network.

“It’s not a lot of data for cell transmission, only a few kilobytes at a time,” said Dr. Matthew Perras, a geological engineer working in a Civil Engineering Department at York University. Dr. Perras specializes in rock mechanics, which is a sub-discipline of geotechnical engineering. He said the goal is to track the impact of daily and seasonal climatic variations on the cracks in the rock.

[Related technology: Nutanix Xi IOT]

The Libelium system is a cost-effective solution that offers a wide range of durable plug-and-play sensors which can be reprogrammed remotely.

“So far they’re standing up well to the harsh conditions and giving reliable data for a fraction of the costs and with less headaches than making them ourselves,” Perras said.

“It’s a great tool for researchers, as you can build it up slowly component by component, adding more stations and linking them together as funds become available.”

Remote programming is also a plus, he said, since the team periodically needs to make adjustments to the monitoring program that records the data.

“We are doing the research from Canada, so we cannot just pop over for a few days to make tweaks to the system that is installed halfway up the cliff face,” said Perras.

The team also has a thermal imaging station and a Raspberry Shake 4D seismograph set up at the base of the cliff near the tomb entrance. With four separate sensors, it can detect strong local events such as rock falls and earthquakes, as well as seismic events over 9,000 miles away. A Raspberry Shake 1D geophone (a type of seismic sensor) sits about 7 meters below the surface in a different tomb, which was built during the reign of Amenhotep II at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna (TT95), another part of the Theban Necropolis famous for its Tombs of the Nobles.

Dr. Matthew Perras, left, and his team test and instal sensor equipment.

The results suggested that the width of the crack being monitored is affected by environmental variables such as relative humidity and the temperatures of both air and rock, which are affected in turn by wind and sun radiation.

“The IoT technology and sensing in general is opening up new insights into rock behavior that were not possible without monitoring at high volumes and over long periods of time,” Perras said. “Monitoring over years is difficult for a number of reasons, but now at least we have the technology to do so.”

Dr. Matthew Perras, top, and his team test and instal sensor equipment.

Perras believes remote monitoring technologies can help other UNESCO world heritage sites that have geological hazards.

“As the sensor and IoT data acquisition costs come down, we should be monitoring all kinds of sites, not just archaeological ones,” he said. “The systems could be deployed along roadways where landslides may occur, or in the mining industry.”

Already, a company called YieldPoint, with experience in making sensors for the mining industry, has donated devices for a monitoring station at another tomb (TT95) at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna. To detect movement caused by heating and cooling cycles between two pillars, and between a pillar and the tomb wall, they need micrometer accuracy, and Perras says YieldPoint’s custom solution is working well.

Julian Smith is a contributing writer.

Learn about Nutanix Xi IoT, which provides simple, scalable, secure edge intelligence for real-time analysis.

© 2020 Nutanix, Inc. All rights reserved. For additional legal information, please go here.